This article was written for the Adams County Historical Society during the 150-year Battle of Gettysburg anniversary and was origonially published in the Gettysburg Times.

The armies had gone, but the human suffering remained. A heavy rainstorm on July 4, 1863 had washed the blood from Gettysburg’s sidewalks, yet the town could not be made clean. The citizens of the town were in trouble. Food and water continued to be scarce, and the 24,000 wounded soldiers that had been left behind had to share the meager resources that remained. Some outlying farmers attempted to help, but only after charging both soldier and civilian exorbitant prices for their goods and services. A loaf of bread was being offered for a dollar, rather than a dime. A cup of milk was being sold for a quarter, rather than a nickel. A wagon ride to a hospital could cost up to twenty dollars. These stories of inhumanity and selfishness were relayed via on-scene newspaper reporters to their readers throughout the northern states, and a poor impression of the area and its citizens lasted for years thereafter. In actuality the vast majority of the people of the area and, especially those citizens who lived in the town itself, conducted themselves admirably and humanely. Still the crisis atmosphere continued.

Help finally arrived for the people of Gettysburg in the form of several organizations, both secular and religious. Some of the organizations concentrated on caring for the wounded of their individual states, such as New York, Indiana and Massachusetts, while others were more eclectic and cared for the wounded of both the Union and Confederate armies regardless of state affiliation. Two groups that stood out because of their early arrival and their trained nurses were the Patriot Daughters of Lancaster and the Daughters (Sisters) of Charity from Emmitsburg, MD. However, it was the arrival of two national organizations, the U.S. Sanitary Commission and the U.S. Christian Commission, that finally relieved the primary concerns of starvation and care for the thousands of wounded. Their Gettysburg headquarters were set up in the Fahnestock Brothers’ store and the Schick/Stoever building, respectively. Mornings would find lines of wagons stretched for many blocks through the town. These wagons would be loaded with all the necessities of survival and then dispatched to town buildings or outlying farms where the wounded lay.

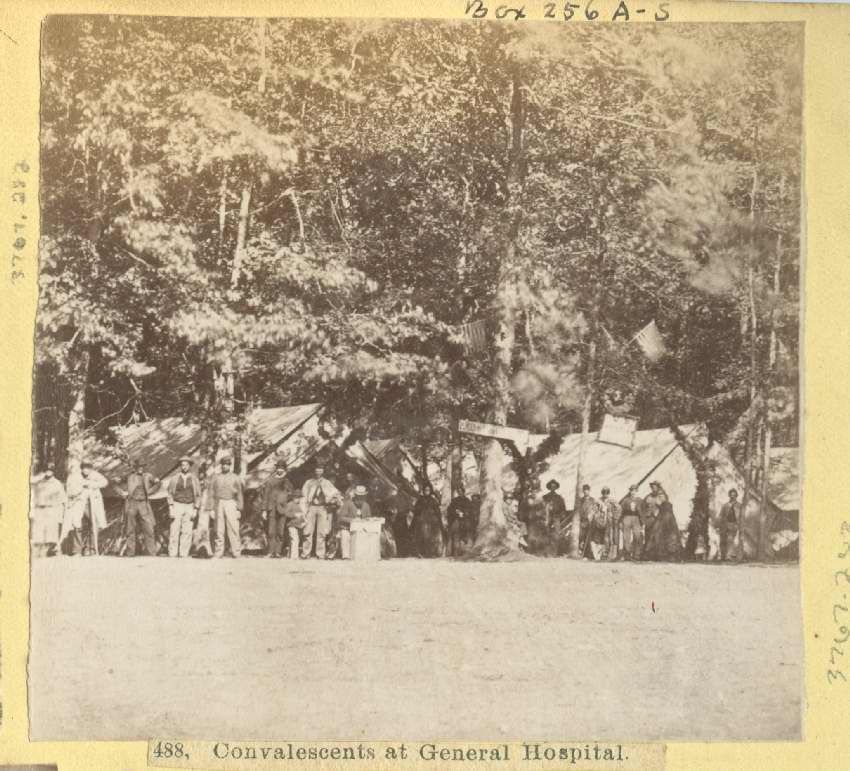

Following the repair of Gettysburg’s railroad bridge that had been burned by the Confederates, “car-load after car-load of supplies were brought to this place”. Food, liquids, bandages and clean clothes were now available. One of Gettysburg’s youth wrote after the battle that if not for the supplies provided by the Sanitary Commission, his family would have starved. Also the arrival of additional doctors and nurses helped relieve the pain and suffering of the wounded in the area. Plans were also made to transport the wounded soldiers to a large hospital complex, to be named Camp Letterman that would be located off the York Turnpike in close proximity to the railroad.

Yet Gettysburg’s trials continued with the arrival of hundreds of sightseers, relic collectors and families searching for the dead or wounded. These incursions began almost immediately after the battle and lasted for several months. Because of the many wounded, beds were already scarce, and many of the visitors had to resort to less than stellar accommodations to include stable lofts, backyards or even the back streets of the town. Although the stench of battle and death continued to fill the air, Gettysburg’s “comeback” had begun…